I came across a fascinating video by Stephen Travers about how to handle overwhelming detail in visual art (sketches and drawings) and I thought there might be something to learn there about how we create abstractions in our software.

Like an artist, a software developer is tasked with expressing the nuance and complexities of the real world in a way that a computer (and other humans) can understand. If we focus only on making something a computer understands, then the code gets more and more complex (harder and harder for a human to understand). It’s difficult to change something you can’t understand, so increasingly complex code means code that is more and more expensive to change.

Since it’s good for our customers (and in turn, our business) to be able to change and improve our code, we invest in expressing the code in ways that computers and people can understand.

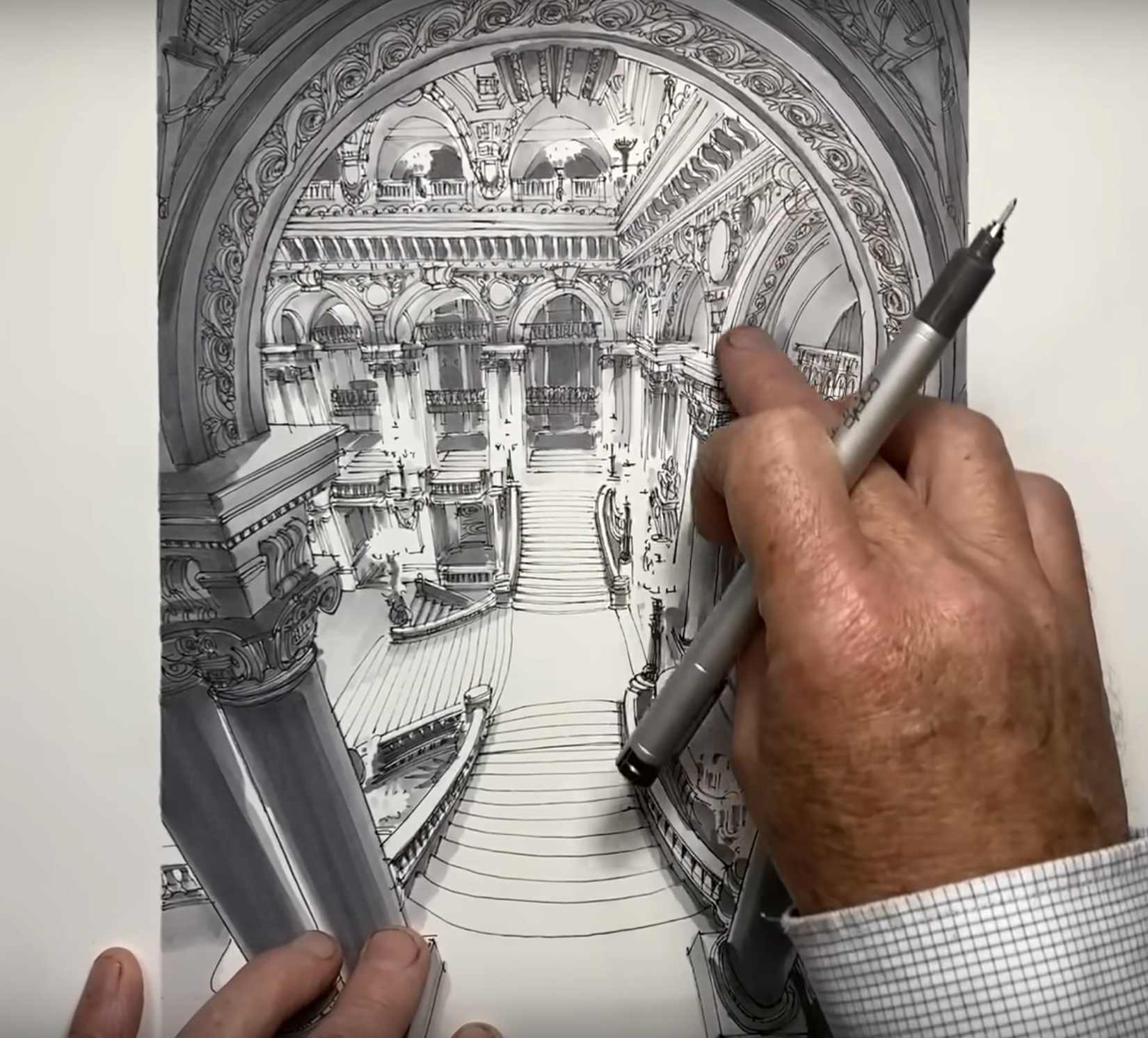

When I saw the intro to Stephen’s video, it struck me that he’s working on the same challenge: how do I express this complexity in a way that still conveys the essential details but without overwhelming the artist creating it?

This blog post reviews some of Stephen’s insights about managing complexity in art, and applies those insights to writing software.

In this video, Stephen uses a scene of a tangle of wildflowers as an example for how to sketch a detailed image in a way that our brains can understand. The steps Stephen follows are similar to how we might approach a software abstraction. This post summarizes the method Stephen teaches, but from the view of a software crafter.

Throughout this post, all quotes and images are from Stephen Travers taken from the YouTube video linked above.

If you find this post interesting, consider liking Stephen’s video on YouTube.

TL;DR

- Study concrete examples to understand the subject

- in art: sketch a detailed view of different aspects of the subject in isolation from the rest of the scene (use light or space to separate the subject)

- in software: unit test specific usage scenarios in isolation from the rest of the application (use test doubles and inversion of control to separate the subject)

- Identify essential details of the subject

- in art: assess what visual characteristics are distinctive – those will be repeated in the background

- in software: refactor the working code to hide everything except the important characteristics. We’ll use this simplified interface throughout the application when we refer to this component.

- Document the subject as a frame of reference

- in art: the detailed drawings in the foreground serve as an explanation for that the simplified detail in the background represent. We interpret the simplification in light of the detailed foreground examples.

- in software: the unit tests show how the abstract interface relates to behaviour. People reading the code can understand the subject by reading the tests.

- Use the abstraction

- in art: repeat the essential details to create the effect of the full thing without recreating the full thing

- in software: integrate the component with the application by referring to the interface. The rest of the application sees only the essential detail that is exposed through the interface; the rest is hidden.

In both art and software, if we attempt to recreate the full detail of a thing every time we refer to the thing, we will become overwhelmed. The world is too complex. Instead, we study the thing, identify essential characteristics, and refer to those characteristics as a proxy for the real thing. In communicating with others, we share a few illustrative examples of the real thing and our pattern-matching brains substitute that detailed example in place of the simplified proxy. This lets us recreate complex real-world situations without being overwhelmed by recreating the full complexity of the real world.

The following sections say the same thing in more detail and with examples.

On unit tests

We need to make it really easy for people looking at a fairly complex scene to know what’s happening, what’s going on, what they’re looking at.

Stephen describes using shadow and silhouette to separate a few detailed flowers from the tangle of flowers. He explains how the final picture will be chaotic, but the viewer needs to see a few very clear flowers to make sense of the chaos. The initial examples help our brain’s pattern-matching to interpret the detail further back in the drawing as flowers.

In software, we do something similar with unit tests. We’re writing complicated code that has a lot of moving parts. We can make the complicated code more clear by providing a few clear examples that are isolated from the rest of the complexity. We use test doubles like mocks and spies like Stephen Travers uses shadow and silhouette: it adds definition to our subject.

Whether we are the authors of the code, or newcomers reading it for the first time, those independent examples in the form of unit tests help us form our first ideas about what this component does.

Stephen goes on to explain that we need an attention to detail here:

We’re trying to give the eyes of the observer some details that stand out really quickly and really easily that the brain will also then find it really easy to attach meaning to. In that way the complexity of the line work, of the detail won’t be overwhelming.

Focus on a few actual blooms, and draw them in detail. I don’t just draw a cartoon daisy.

In this stage, Stephen is studying the flowers. He notices that they all point towards the sun, but some of them have the tops of the petals facing the viewer, and others the bottom or side on. He notices some open flowers, some buds, and the stems. Through these clear examples, he’s getting an idea of the variation in the scene. In the same way, our unit testing is a discovery exercise where we learn about new edge cases in the software we’re writing. After a thorough session of test driven development, we understand the nuance of our code well because we’ve written out an example of each of the quirks.

On interfaces and patterns

Since Stephen has studied the flowers, he has identified they are composed of:

- flowers

- buds

- stalks

He’s also observed that flowers come in roughly three variations: facing the observer, facing away from the observer, and side-on to the observer.

For every part of the scene, there is some level of lightness (or darkness) that gives a sense of depth.

Stephen then works through the drawing, adding flowers, buds, and stalks, varying the lightness to convey depth, and varying the orientation of the flowers.

As software developers, we could model this scene as a bunch of parts of the scene made up of those components. For example:

enum Orientation {

TOWARDS_US,

AWAY_FROM_US,

SIDE_ON

}

class Flower {

Orientation orientation;

}

class PartOfScene {

List<Flower> flowers;

List<Circle> buds;

List<Line> stalks;

Percentage lightness;

}

This model is an abstraction of the scene. There is more detail in the image (and in the real tangle of flowers). Stephen explains that as an artist, to convey all the detail throughout would be overwhelming. In my view, this act of summarizing is part of the purpose of the art: I’m interested in seeing how Stephen summarizes a tangle of wildflowers. What does Stephen think is important about them?

I can’t take in every blade of grass and every petal in a glance, but I can take in his drawing in a glance. He has given a handful of isolated, illustrative examples in the foreground and then expressed the overall effect: the flowers are tangled together, pointing generally towards the sun with some variation, and a mix of buds and open flowers.

As software developers, we use abstractions to refer concisely to complex systems. When we’re deciding what to include in the summary, it’s helpful to study several real examples (not caricatures; high fidelity examples) and learn the general pattern from them.

In software, we could produce an abstract model like this by following Stephen’s pattern:

- Study concrete examples (not caricatures) in isolation: write independent unit tests that showcase one nuance of the component

- Understand the essential parts of the subject: refactor our code to hide everything except for the things that vary meaningfully

- Replicate the effect/essence of the thing (not the full detail of the thing): as we start using this component elsewhere in code, we can ignore all of the hidden details. We consider only the essential parts; the abstraction; the interface.

Stephen summarizes his approach like so:

I draw the effect of the detail rather than the actual detail

In software, we can ask ourselves “how does a consumer experience this code”, and make that our abstraction. It doesn’t matter what the code is, it matters how it affects its neighbors. Hide everything except that which is applicable to the neighbors.

Finding the essence

Stephen works through several examples where he identifies what is the aspect of the architecture that is important as someone looking at it. This is not a process of scientific analysis; Stephen has insight about what about the thing makes it interesting to look at. He talks about patterns repeating, shadows between supports, the effect of perspective on decorations, symmetry, shape, etc.

This is the part that takes insight and artistry: how do you look at a thing and say “if a stranger were here, I bet they would be moved by this aspect of it”. The artist expresses what they’ve experienced.

In software development, we may not invest so much in artistic expression, but there is a principal here that can serve us well in keeping our code simple and easy to change. If we can express ourselves well in code, then our code will be easier for others (and our future selves) to change, which means we can serve our customers better.

Let’s take a look at an example of a method signature that we could abstract in many different ways depending on how it is used (“experienced”) in calling code. The method is called “qualt” which doesn’t mean anything, it’s just an imaginary function.

int qualt(String algorithm, String name) {

// Qualtize name according to the algorithm

}

Suppose our code takes an algorithm and a name from user input (unconstrained – they can be almost any text) and then shows them the qualt number for that input. In that case, our current function already has a pretty good abstraction: take in two strings, get a number back, end of story.

Next, suppose the algorithm and name can be anything, but our code has to do different things based on the result. If the qualt number is even, then we send out special notifications. If the number is greater than 1000, then the customer is redirected to a different part of the user interface. The code and the customer never actually see the qualt number directly. In this case, we might want the following:

interface QualtNumber {

boolean requiresNotification();

boolean requiresRedirectToADifferentPartOfTheUI();

}

QualtNumber qualt(String algorithm, String name) {

// Qualtize name according to the algorithm

}

Here, because of our insight about how the code is experienced by the caller, we

replace int with QualtNumber which has methods to understand the meaning of

the qualt number. The calling code can say if (qualt(algorithm,

name).requiresNotification()) { /* ... */ } instead of if (qualt(algorithm,

name) % 2 == 0) { /* ... */ }. The essence is better communicated.

Similarly, suppose the customer does not provide any text for the algorithm, but the have to choose from “connigers”, “clairiose”, or “aritionated”. We may want the following signature:

enum QualtAlgorithm {

CONNIGERS,

CLAIRIOSE,

ARITIONATED

}

QualtNumber qualt(QualtAlgorithm algorithm, String name) {

// Qualtize name according to the algorithm

}

Each of these changes came from asking what about this code is important to the caller? We want to think about how it is experienced, and understand the essence. This takes imagination, and offers the reward of expressive code that communicates the essence of the thing without bringing along all the complexity.